THE CURBSIDE CRITERION: ALL THAT MONEY CAN BUY

(Here at Hammer to Nail, we are all about true independent cinema. But we also have to tip our hat to the great films that continue to inspire filmmakers and cinephiles alike. This week, Jonathan Marlow takes a journey to hell and back via the Criterion 4k Blu-Ray release of ALL THAT MONEY CAN BUY.)

“Yes! It could even happen to you!”

Or could it? Are you likely to [spoiler] sell your soul to the devil (if you haven’t already)? Is that sort of thing even done these days? Is the devil still interested in such a pact or are there plenty of folks already heading that direction without the need for a soul-bargain? Granted, with “heaven” and “hell” remaining primary concerns of the afterlife for the faithful, it stands to reason that souls are still a valuable commodity for those nefarious bureaucrats downstairs.

Regardless, if the title ALL THAT MONEY CAN BUY (1941) lacks some familiarity, you’d likely know the tale as THE DEVIL AND DANIEL WEBSTER (as the original Stephen Vincent Benét short story was titled). It initially started production as A CERTAIN MR. SCRATCH in order to avoid any potential confusion with the contemporaneous DEVIL AND MISS JONES (not to be confused—not that it would, necessarily—with the much-different DEVIL IN MISS JONES three decades later). MR. SCRATCH was scratched and HERE IS A MAN became the titular choice. Until it wasn’t. ALL THAT MONEY CAN BUY was the film-title upon initial release and then it was slightly re-cut and re-released as THE DEVIL AND DANIEL WEBSTER. Later still, in a 1952 reissue, it was re-titled simply DANIEL AND THE DEVIL. Given that the aforementioned Mr. Webster is largely [another spoiler] a secondary character until the third act, ALL THAT MONEY CAN BUY is likely among the best of the assorted naming options. A CARNIVAL OF SOULS for the soul-deficient.

It wasn’t always available to be seen in its optimal form, admittedly. Or, contrary, it was usually available in an unintended form. Criterion released a Laserdisc way-back-when—goes without saying, Laserdisc-wise—that restored the film to its original running time (from 85min. to 105min.), most noticeably recovering a trio of negative-image insert-shots which foreshadow the arrival of Mr. Scratch and his inevitable influence. The latest Blu-ray edition derives from a German nitrate print with missing footage salvaged from a dupe negative. The integration of the disparate materials is largely seamless, giving audiences the opportunity to experience the film as it was seen by its earliest viewers more than eighty years ago.

For the uninitiated, ALL THAT MONEY CAN BUY is a “fantasia on American themes” or an “American Pastoral” by-way-of FAUST. Set in Cross Corners, a village of casual conformity, populated by a God-fearing people with an overwhelming belief in a merciful God. In essence, ATMCB maps war-time concerns of the 1940s to the 1840s by placing an otherwise “good” man—in the form of Jabez Stone (as portrayed by James Craig)—in a “bad” situation of financially challenging times, inadvertently running his farm into ruin due to circumstances beyond his control. His wife, Mary Stone (Anne Shirley), is a proverbial product of the same archetype as Janet Gaynor circa SUNRISE: A SONG OF TWO HUMANS: a wholesome individual who emotionally supports her husband even when the rationale for such support is in evident need of collapse. Enter Mr. Scratch (the irascible Walter Huston) with a nefarious bargain promising all the success that money can, natch, buy. Buy, Jabez does. He consolidates his neighbours’ farms after a blight destroys their crops but spares his land. The townfolk ultimately begin to work for him and, along the way, lose their self-respect and grow to despise their “saviour”-turned-ersatz-boss.

At this interval arrives our intended hero, Daniel Webster (Edward Arnold) aka Black Daniel, in a portrayal that would hardly fly in our cynical times—of an honest politician and lawyer—as a likeable fellow who cannot be bought. The devil attempts to tempt his with a pathway to the Presidency and he’ll have none-of-it. He strikes-up a genuine friendship with Jabez and the Cross Corners couple make Webster the godfather to their forthcoming child, the baby Daniel. On the birth of the boy, Mr. Scratch swaps-out the Stones’ housemaid with the French-y temptress Belle Dee (the spectacularly sinister Simone Simon). All, ahem, hell breaks loose accordingly. Belle serenades the infant (in French) a lullaby of, “Satan is your father… and all Hell is your world…”

No further indication of how far Jabez has fallen is as evident—outside of his constant “Consarn it!” cursing—as his willingness to gamble on the Sabbath. The non-mighty have weakened. It is here that we begin to penetrate Mr. Scratch’s larger intent. As the duration of the bargain begins to wind-down, he continues his trickery of persuasion with even a common song-and-dance (with incongruous orchestrations of popular tunes such as “Pop Goes the Weasel” long before THE PRISONER). The devil is a fiddler, no less! The speculative sands of the hourglass signal a need to renegotiate the terms of the deal and Mr. Scratch proposes an addition of the soul of the son for an extension of the agreement. Jabez has little inclination to shake hands with the devil a second time.

At loose ends, Mrs. Stone disappears to Marshfield, Webster’s property, to convince the Senator to save her wayward husband. Thusly, the crux of the narrative transforms into a procedural, fabricating a makeshift courtroom to defend Mr. Stone against damnation. Jabez is tried by a jury of not-peers, including Revolutionary War traitor Benedict Arnold, John Hathorne (the Salem witch-trials judge and great-great grandfather of Nathaniel Hawthorne) and Stede Bonnet (the same “Gentleman Pirate” of OUR FLAG MEANS DEATH). Webster, in-between an ambitious ingestion of liquor, provides a spirited defence, removing his jacket and concluding, “Gentlemen of the jury, don’t let this country go to the devil!”

Mr. Scratch has a case to make as well. “When the first wrong was done to an Indian, I was there. When the first Slaver put-out for the Congo, I stood on deck.” If temptation is the aim, he evidently requires little effort to persuade much of humankind. However, [spoiler?] Webster is a skillful orator and even a jury of deceased malcontents have an inkling of goodwill remaining in their dark solitude.

For a story already overflowing with unusual approaches, the final scene [and final spoiler] ends with an unexpected breaking-of-the-fourth-wall, serving to unsettle the viewer one final time—bringing them directly into the story—before they head for the exit (or hit the “power off” button on their remote control).

If such unconventionality is the norm of its end, it is somewhat signaled at the start in the method in which the actors and crew are listed, all are identified as collaborators (“in front of the camera” and “in back of the camera”), without attributed roles in the opening crawl. This is no normal film, Hollywood-wise or otherwise.

Despite the depths of a war that preoccupied much of the rest of the world, the U.S. (and Canada, Australia and elsewhere) were still on the sidelines, supporting the efforts in material ways without direct military intervention (not entirely unlike the present situation vis-à-vis Ukraine and Russia or Palestine and Israel). As such, the cinematic releases of that year had little equivalent over the four-or-more years that followed. ALL THAT MONEY CAN BUY is one-among-many highlights of 1941. It was preceded at RKO Radio Pictures by the vastly better-known CITIZEN KANE and the films share not only a studio but an editor in Robert Wise and identical composer, the legendary Bernard Herrmann (both of whom would continue on to their next RKO production, THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS). Regardless of its assorted titles and various durations, the journey of DANIEL WEBSTER to the screen was considered a success. Director (and former silent-era actor) William Dieterle and cinematographer Joseph August, following the wartime preoccupations, reunited on PORTRAIT OF JENNIE in 1948—scored yet again by Herrmann—and might’ve worked together thereafter if not for August’s passing shortly after PORTRAIT was completed. Perhaps, under other circumstances, they would’ve followed-up ALL THAT MONEY CAN BUY with another Stephen Vincent Benét adaptation (although the author died of a heart attack less than two years after the film was released).

As is often the case, if the restoration itself is not merely sufficient to satisfy, the Criterion release doesn’t skimp on bonuses. The most significant of these additions are earlier radio adaptations of THE DEVIL AND DANIEL WEBSTER (1938) and DANIEL WEBSTER AND THE SEA SERPENT (1937), both with scores by the aforementioned Bernard Herrmann. For Herrmann aficionados, this pairing of rarities alone is worth the cost of acquisition.

ALL THAT MONEY CAN BUY

dir. William Dieterle [106min.] RKO Radio Pictures | Criterion Collection

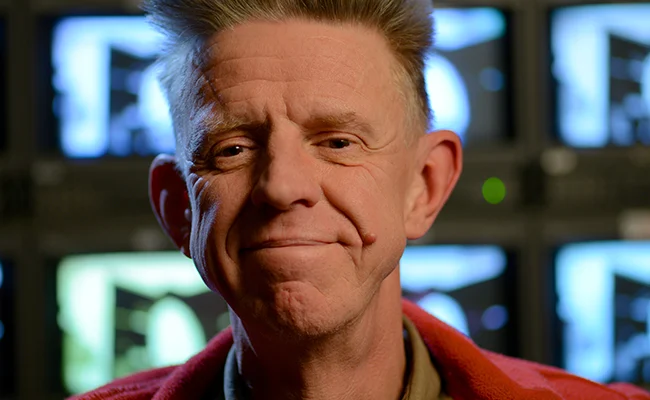

– Jonathan Marlow (@aliasMarlow)