A Conversation with John Waters (CRY-BABY)

Baltimore-based filmmaker John Waters—aka “The Pope of Trash”—began his career in the 1960s as a provocateur, directing a series of proudly outrageous features on microscopic budgets, with drag queen Divine as his frequent star. His many early works include Pink Flamingos and Female Trouble, both once reviled by the mainstream yet now available via beautiful high-res restorations as part of the prestigious Criterion Collection. By the 1980s, Waters’ star outside of the experimental underworld was on the rise, thanks to features such as Polyester and Hairspray. The year 1990 saw Waters tackle his first big studio pic, Cry-Baby, with Johnny Depp in the lead. And now, courtesy of Kino Lorber, that film is coming out (on May 28 of this year) on Blu-ray in a beautiful new 4K transfer.

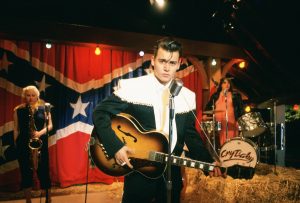

The film—set in Eisenhower-era America—follows the titular character (Depp) as he steps out of his peer group to date a “Square.” He’s a “Drape” (someone who would be called a Greaser outside of the Baltimore area), dressed in leather with a styled pompadour. His inamorata is Allison (Amy Locane), who is tired of the same old Square thing and wants to break free of the chains of conformity. With a soundtrack filled with both 1950s hits and original music composed for the movie, Cry-Baby proves an intriguing combination of Waters’ trademark rebelliousness and more conventional cinematic traditions (gleefully subverting those conventions along the way).

As a Baltimore resident, I couldn’t help but jump at the chance to interview Waters ahead of the Blu-ray release. We chatted via Zoom. What follows is a transcript of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

HtN: So, you had been making films since the 1960s, and by the time you made Cry-Baby had garnered some mainstream success in the ‘80s. But this was your first actual studio picture, made for Universal and Imagine, and I’m curious what was that transition to a much bigger budget like for you?

John Waters: Shocking, in a way, though Hairspray was already kind of there. Hairspray was a a New Line movie. They were a Hollywood studio, but not like Universal or that kind of thing. And so it was amazing to us. I remember the first day, when we got on the set and saw all this equipment…and we had Johnny Depp and we had all these stars, we had trailers, we had all this kind of stuff we never had before. It was inspiring and exciting for us, you know? And it was great because we brought Hollywood stars along with the same people who had always worked with me in the past, folks like Van Smith and Pat Moran and Vincent Peranio. They still did all the main jobs.

HtN: That was going to be my next question. Did you have any issues with the studio allowing you to bring along people like Pat Moran and your cinematographer Dave Insley?

JW: No, not really, because it was the only time ever in my entire career when every Hollywood studio wanted to make my next movie. Because Hairspray had just happened and it was perceived as more of a hit than it actually was. But that’s all that matters in a certain moment in Hollywood. So they all wanted to make my next film, which never happened again. It was exciting to have them bidding against each other. Amazing!

And I had been taught how to pitch by my friend Jeff Buhai, who directed Revenge of the Nerds, and I had Bill Block as my big agent and Tom Hansen as my first Hollywood lawyer and they were great. They steered me the right way and I learned how to do it, luckily, because I had been promoting my own movies forever. So it wasn’t that hard for me to go in and pitch a movie.

A still from CRY-BABY. Credit: Henny Garfunkel

HtN: And you then also gave people like Dave Insley and Rachel Talalay a good start. She went on to do other things in the 1990s, including one of my favorite 1990s films, Tank Girl.

JW: Right, right. She started out as a PA on Polyester. And then did some of the Nightmare on Elm Street films.

HtN: So in this film you had both original and prerecorded music. What kind of guidance did you give to music supervisor Becky Mancuso for finding songs from the era?

JW: Well, she knew her stuff. She knew the right people to go to who were involved in that original music in the ‘50s, and she knew her stuff. And I did, too. So that went very smoothly, actually. And I think the original music in Cry-Baby is also amazing. I think they did a great job.

HtN: Which brings me to a question about the stage musical, which I’ve never seen. What was that like?

JW: It is really good, too, and is probably closer to the movie than even Hairspray was. But the problem with the musical is that it was a Broadway musical for the whole family, but with frontal nudity. And that may be a fun thing to watch, but it’s a problem when touring regional theaters in front of high-school students. I think it will come back one day because I think the music is great.

HtN: But…your movie doesn’t have full-frontal nudity.

JW: No, it doesn’t. But in the musical it was innocent. It was skinny dipping. It wasn’t any sexual thing.

HtN: Right. Did they include in the musical the extended French-kissing scene that’s in your film?

JW: Yes, that’s in there. There’s a whole song about “Can I kiss you with tongue?” and the whole chorus of everyone sticking their tongues out. (makes sound of tongues flapping).

HtN: (laughs) Well, now I definitely want to see it.

JW: But when you look at that scene now, can you imagine asking people to do that? You’d need 5000 intimacy experts on set. And not one of those extras complained one bit and they had to French kiss with strangers all day.

HtN: So, given Johnny Depp’s status at the time as a huge teen idol, did you have any challenges in getting him for the movie?

JW: No, he wanted to do it because he hated being a teen idol and thought we could end it, and we did in a way because we made fun of it. And he embraced it and made fun of it. And that’s how you always change your image. And so did many people in the movie: Patricia Hearst did; Traci Lords did. I’ve made fun of my image my whole life. That’s how I’ve gotten away with it.

Johnny Depp in CRY-BABY. Credit: Henny Garfunkel

HtN: I listened to the commentary that you did back at the start of COVID for this film, and you talked about about the casting and how Tim Burton came and saw this film and…

JW: He did, before it came out, he saw dailies and stuff and then put Johnny in Edward Scissorhands.

HtN: So you really helped launch that next stage of his career.

JW: Well, if you look at Johnny now, he’s so great in the movie. He’s such a star and even though he’s making fun of being an idol, God knows it’s obvious why he was one.

HtN: Did you have any part in casting the people who were dubbing the singing voices for both Depp and Amy Locane?

JW: Yes, very much, because the woman doing Amy Locane, Rachel Sweet, had done Hairspray. She sings the title song in Hairspray, and she was great and the guy that played Cry-Baby [James Intveld] was the real-life Cry-Baby. I didn’t know him, but they brought him to me and he was absolutely perfect.

HtN: And the voices do a pretty good job of matching how the actors sound when they’re actually speaking.

JW: And the lip-syncing’s really great. We had a lip-sync coach. I never knew there was such a job. Like who, as a kid, says, “I wanna grow up and be a lip-sync coach”? but if you watch Amy Locane and everybody else, they lip-sync really well, and it’s not easy to do that.

HtN: No, I can’t imagine it is. So, I live in Baltimore, but I’m a little younger than you. Where does the term “Drape” come from?

JW: From clothes that were a bit baggy, like zoot suits. Basically, drapey clothes that hung low. If you ask anybody in Baltimore my age or older, “Were you a Drape or a Square?,” they won’t hesitate. Square was like “Preppy.” Drapes were more blue collar. It was a class issue; the Drapes were like Elvis rockabilly delinquents. The Squares were preppy, but they were cool, too.

HtN: But it’s a term that was kind of unique to this area, right?

JW: Well, I don’t know that, but in Baltimore it was very much a thing. And maybe you’re right that in the rest of the country, they might say Greaser, while we said the word Drape.

HtN: Speaking of the Drapes, you have that detail, which I understand is period-accurate, of the Confederate, or “rebel,” flag. What was the significance to the Drapes of having something like the rebel flag as part of their background?

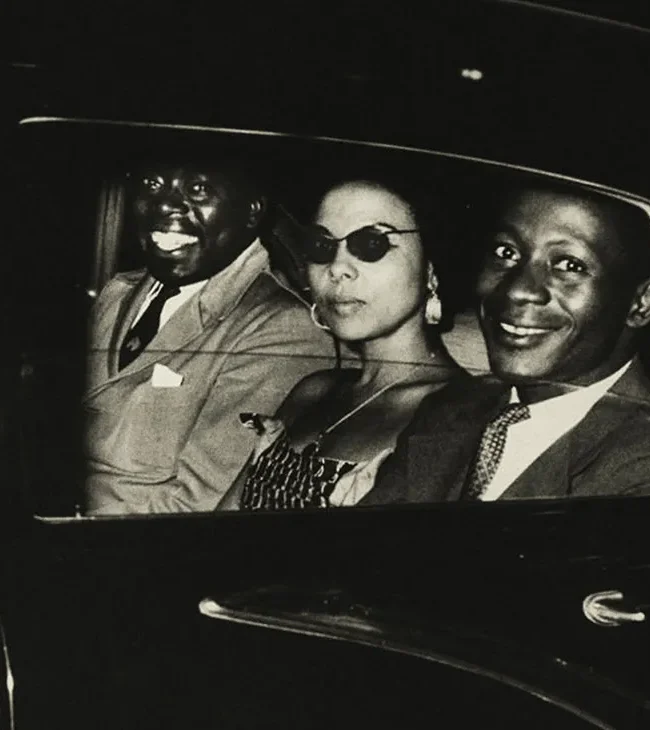

A still from CRY-BABY. Credit: Henny Garfunkel

JW: Well, it was not thought of as completely racist then, or at least I don’t think it was, but I added the Black gang in there, as well: the “Conks.” That would have never happened.

HtN: Right. You did that to make them less racist?

JW: Yeah. Well, but I didn’t ever say that the Drapes were racist. Because back then if you had a rebel flag it didn’t necessarily mean what it means today. I guess it probably did to African Americans, though. But I had a Black gang in there with a similar kind of hairdo, even if that would have never happened, with them fighting and partying together in 1954. So I made it better, just like I gave a happy ending to Hairspray, that didn’t really happen.

HtN: You have that great 3D scene using footage from The Creature from the Black Lagoon where Hatchet-Face busts out of the screen. Is that particular film a favorite 3D film of yours from the ‘50s?

JW: Yes, it was a favorite movie of mine when I was young, and that is the biggest laugh in the movie.

HtN: It’s great. I love occasionally showing 3D films to students in my classes. Do you have any other favorite ones from that era?

JW: I do, but they’re porn.

HtN: (laughs) So, I love the scene where you bleep the word f*** out twice and then you don’t bleep it when Patty Hearst says it.

JW: The rule then was you could say f*** twice in a non-sexual way but could never say it once in a sexual way. So to make that joke work, you had to say it three times, so we went around the MPAA and bleeped it and they fought us on it. But we won.

HtN: It’s a really great joke.

JW: I didn’t think it was funny at the time, though.

HtN: Well, it does work, at least today, as a great laugh. So, you have some terrific stunt-casting in this film, like Willem Dafoe playing the prison officer.

JW: We invented it. But you know what? I hired people that I thought were great. I didn’t hire anybody that I thought was bad. I hired everybody in it that I think did a great performance, but they had to come along for the ride. It was a satire on casting.

I don’t think there was the term “stunt-casting” before we did it, but I didn’t pick anybody that wasn’t good. I think they’re all good in it.

HtN: I agree. Now, where does that line “Beauty, brains, breeding and bounty” come from?

JW: I hate to tell you, but my grandmother used to say that to us. She’d say, “That’s what you need: the 4B’s – Beauty, brains, breeding, and bounty.” We always rolled our eyes and said that in our family. But my grandmother believed it and told us that.

And the dancing class was…I had to go to cotillion when I was young, which gave me the rage I had to make things like Pink Flamingos. No one said the word “charm school” in fancy neighborhoods, but that place was very much like where I had to go to dancing class and everything else when I was growing up. And so that was my revenge on that.

HtN: Speaking of dancing, my favorite choreography in the film is the choreography of the Squares. I think what you make them do is so funny, and I particularly like that “Sh-Boom” scene.

JW: Well, the bunny-hop is a real dance. We had to do that in dancing school, in cotillion.

HtN: And how about the “Sh-Boom” choreography?

JW: We had a great choreographer, but all those dances were real. Pretty much all the stuff that they did in that movie, people really did back then.

HtN: Well, those actors playing the main quartet of Squares do a wonderful job. One of them I understand is Norman Mailer’s son, right? The guy who plays the lead antagonist?

JW: Yeah, he’s the main one. He’s the villain. And he’s great. And he gives a wonderful interview on the new set that’s coming out.

HtN: I haven’t yet seen the Blu-ray because it wasn’t quite ready to be sent out yet. What else is on there?

JW: Well, there are two versions of the film. Because after the test screenings, we did reshoots, though even after we did the whole thing and spent $1,000,000 it tested exactly the same. It did make some things better and a little clearer, but it didn’t really matter. There was one musical number that was cut out that you can see on the disc. But wait till you see all the interviews with everybody. That’s what’s pretty amazing.

HtN: I love watching interviews from people who worked on a film. So, final question: where does this film, at this point, personally sit for you in your canon?

JW: Well, it’s the film that many young people tell me was the entry point to seeing my movies when they were young. Because it’s one they could watch and they were thrilled by it and it made them feel good about themselves if they didn’t fit in and all that kind of thing, so I’m happy about that. And to me, it’s my first Hollywood movie. I’m proud of it.

HtN: I can’t wait to see the disc! Thank you for talking to me.

JW: Sure. And thank you!

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)